The latest release of hevm introduces symbolic execution features which can be used for checking smart contracts for correctness, step through the execution space of live contracts, or prove equivalence between them.

In this tutorial we will show how to use the new capabilities of hevm, and discuss some of its unique features as a symbolic execution engine.

Table of Contents

About hevm

hevm is an EVM interpreter originally written with testing and debugging in mind.

It serves as the execution engine for such tools the dapp smart contract development framework and the echidna smart contract fuzzer.

This release marks its first venture into the realm of symbolic execution, developed with composability, practicality and configurability in mind.

Using hevm symbolic, smart contract developers can also find assertion violations in their smart contract or interactively step through the possible execution paths of their smart contracts to explore its full range of behaviours.

The first release of hevm with symbolic execution is experimental and limited, and its proofs should not be relied upon as a formal verification engine for in production code.

Still, we hope that its supported set of features will serve as a helpful tool in developing and analysing real world smart contracts. This release introduces the following features:

- Find assertion violations, division-by-zero errors, out of bounds array access, or other failures resulting in an invocation of the INVALID opcode

- Compare smart contracts for equivalence, searching for cases where the same input would lead to different outputs or storage updates

- Interactively explore the possible execution paths of a contract in a rich command line debugger

- Automatic test case generation

- Analyze deployed contracts, using live state fetched on demand via RPC calls from a local or remote node

Symbolic Execution and Formal Verification

This release is the first step towards making hevm capable of formally verifying smart contracts. hevm can be used to check smart contracts for assert statements, returning a counterexample for assertion violations. But proving the absence of assertion violations is only a small subset of the types of assurances that can be given with formal verification.

More involved claims are more easily specified with the smart contract specification language act, which we will be explaining more in a future blog post.

How does it work?

When an hevm execution starts, it keeps the various buffers and registers of the EVM on symbolic form, building up abstract expressions rather than concrete values as opcodes are interpreted. When the execution reaches a JUMPI opcode with a symbolic argument, it performs an SMT query to see if there is an assignment of variables such that the JUMP is taken, and if there is an assignment where it isn’t. Execution then proceeds along the satisfiable branches until one ends up with all possible EVM end states. At this point, we check those end states against some correctness criteria. In this release, we will mostly be checking the end states for assertion violations, but we can also provide example input for each ending state using the --get-models flag, which can be quite useful for automatic test case generation.

SMT queries are resolved by either z3 (default) or cvc4 (flag --solver cvc4), and the timeout setting can be configured using --smttimeout <milliseconds>. For more information about available settings, you can check out the hevm README or simply run hevm symbolic --help.

If you are curious about the implementation details, you can check out the high level summary in the PR.

In the following section, we will go over a few examples of how to use the new symbolic execution features of hevm.

Installation

To be able to follow along in this tutorial, make sure that you have hevm installed. hevm is a part of dapptools, a suite of command line oriented tools which uses the purely functional package manager nix for installation. First install nix:

curl -L https://nixos.org/nix/install | sh

. "$HOME/.nix-profile/etc/profile.d/nix.sh"

and then hevm along with the rest of dapptools with:

curl https://dapp.tools/install | sh

You should now be able to use hevm:

hevm version

0.40

You need at least version 0.40 to use the symbolic features of hevm.

Using hevm symbolic

The main feature introduced in this PR is hevm symbolic. In its simplest form, it can be used to search for assertion violations in the --code provided. Consider the following example:

contract PrimalityCheck {

function factor(uint x, uint y) public pure {

require(1 < x && x < 973013 && 1 < y && y < 973013);

assert(x*y != 973013);

}

}

We can use hevm symbolic to see whether there exists a pair of uints x and y such that their product is 973013. We can specify a function abi using the --sig flag to let calldata be assumed to be a well formed call to factor:

$ solc --bin-runtime -o . primality.sol

$ hevm symbolic --code $(<PrimalityCheck.bin-runtime) --sig "factor(uint x, uint y)"

checking postcondition...

Assertion violation found.

Calldata:

0xd5a2424900000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000003fd00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000003b9

factor(1021, 953)

Caller:

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Callvalue:

0

With the --debug flag supplied, you will enter into an interactive environment where you can manually navigate through the possible execution paths. Let’s try it with this simplified token contract:

contract Token {

mapping(address => uint) public balanceOf;

constructor(uint supply) public {

balanceOf[msg.sender] = supply;

}

function transfer(address receiver, uint256 value) public {

require(balanceOf[msg.sender] <= value);

balanceOf[msg.sender] -= value;

balanceOf[receiver] += value;

}

}

This time we’ll ask solc for a lot more compiler artifacts which we supply with the --json-file to make the debug view more informative:

solc --combined-json=srcmap,srcmap-runtime,bin,bin-runtime,ast,metadata,storage-layout,abi token.sol > combined.json

hevm symbolic --code $(cat combined.json | jq '.contracts."token.sol:Token"."bin-runtime"' | tr -d '"') --debug --json-file combined.json --solver cvc4

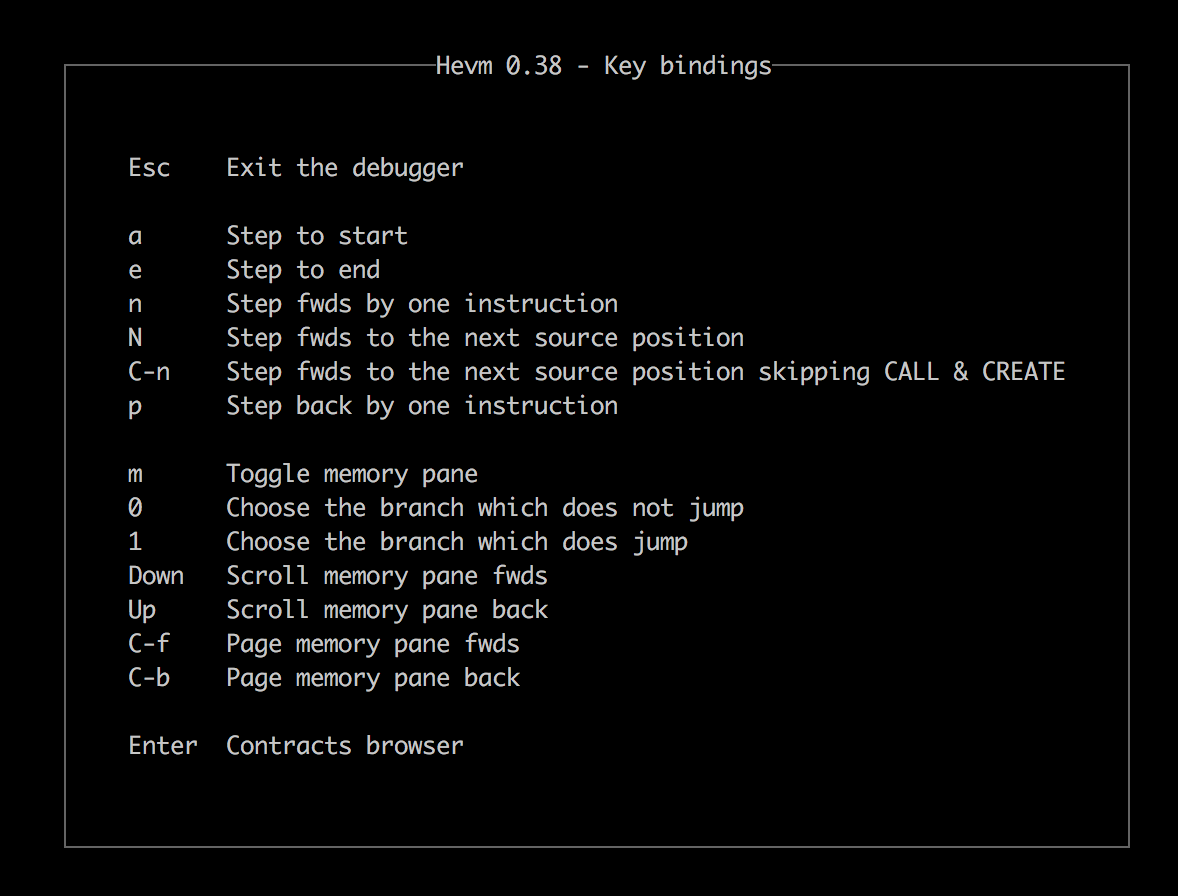

We find ourselves in an interactive environment just like the one shown in the screencast above, in which we can navigate step-by-step using the following key bindings:

Whenever we reach a branching point (JUMPI opcode) with a symbolic argument, hevm will make an SMT query to see which branches are possible. If both branches are satisfiable, we can choose the branch we are interested in by pressing 0 or 1.

Executing against live contracts

It is also possible to explore contracts deployed on chain, by fetching the relevant state via RPC from a URL provided with the --rpc flag.

For example, to symbolically explore the chai contract, we simply need to provide its mainnet address.

hevm symbolic --rpc https://mainnet.infura.io/v3/INFURA_SECRET --address 0x06af07097c9eeb7fd685c692751d5c66db49c215 --solver cvc4 --debug

Unless you are a true EVM whisperer, looking at the bytecode itself will not be the most illuminating experience.

If you have an etherscan API key, you can fetch the source code of the contract and compile it on demand using seth bundle-source:

export ETHERSCAN_API_KEY=$ETHERSCAN_SECRET

seth bundle-source 0x06af07097c9eeb7fd685c692751d5c66db49c215 > chaisrc.json

The resulting json can then be passed to hevm symbolic to provide source maps as we step through the contract:

hevm symbolic --rpc https://mainnet.infura.io/v3/$INFURA_API_KEY --address 0x06af07097c9eeb7fd685c692751d5c66db49c215 --solver cvc4 --debug --json-file chaisrc.json

When dealing with executions over RPC fetched state, hevm offers a different ways of handling storage reads.

The default option models contract storage as an SMT array and simply returns an unconstrained symbolic value for SREADs. It is possible to read and write to symbolic storage locations.

If passed --storage-model InitialS, you can still SREAD and SSTORE values at symbolic locations, but the default value is 0. This model is used automatically if the --create flag is passed.

Finally, using --storage-model ConcreteS, storage will be fetched on demand from a remote node via RPC. As a result, you cannot read from symbolic storage locations.

The concrete storage option is especially useful in situations where a contract is calling an address kept in storage. For example, if you navigated to the join or exit method in the exercise above you noticed that the execution halts with VMFailure: UnexpectedSymbolicArg at the opcode EXTCODESIZE. The pot address we are trying to call from the chai contract is kept in storage, but while symbolically executing, the storage read instead returns an arbitrary symbolic value. If we run the same execution with --storage-model ConcreteS, we fetch the real pot address via RPC and we can get a little further:

hevm symbolic --address 0x06af07097c9eeb7fd685c692751d5c66db49c215 --sig 'join(address,uint256)' --rpc https://mainnet.infura.io/v3/$INFURA_API_KEY --debug --json-file chaisrc.json --storage-model ConcreteS --smttimeout 5000

With these settings we’re able successfully symbolically execute until reaching the line:

balanceOf[dst] = add(balanceOf[dst], pie);

where we suddenly fail again with VMFailure: UnexpectedSymbolicArg, because we end up doing an SLOAD from a symbolic location, which is not possible with --storage-model ConcreteS.

With our current set up, it turns out we must use concrete arguments for dst and msg.sender in order to avoid reading from symbolic storage locations. We can instantiate these arguments to some concrete value, for example one of Vitalik’s addresses, 0xAb5801a7D398351b8bE11C439e05C5B3259aeC9B:

hevm symbolic --address 0x06af07097c9eeb7fd685c692751d5c66db49c215 --sig 'join(address,uint256)' --arg 0xAb5801a7D398351b8bE11C439e05C5B3259aeC9B --caller 0xAb5801a7D398351b8bE11C439e05C5B3259aeC9B --rpc https://mainnet.infura.io/v3/$INFURA_API_KEY --debug --json-file chaisrc.json --storage-model ConcreteS --smttimeout 5000

Automatic test case generation

As we have seen, symbolic execution can be an insightful tool for analysing smart contracts, even in the absence of a specification, or asserts in the code. By exploring the possible execution paths of a program, we can see the full range of behaviour of a smart contract, which can lead us to discover unexpected edge cases or dead code. It can also be used for generating test cases. If we pass the flag --get-models to the invocation of hevm symbolic, it will give us example input data for each path explored. To look at a simple example, consider the WETH contract at 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2. An easy way to fetch its code is via seth code 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2:

hevm symbolic --code $(seth code 0xC02aaA39b223FE8D0A0e5C4F27eAD9083C756Cc2) --sig "transfer(address,uint)" --get-models

checking postcondition...

Q.E.D.

Explored: 3 branches without assertion violations

-- Branch (1/3) --

Calldata:

0xa9059cbb00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

transfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,0)

Caller:

0

Callvalue:

115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007913129639935

Reverted

-- Branch (2/3) --

Calldata:

0xa9059cbb00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

transfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,1)

Caller:

0

Callvalue:

0

Reverted

-- Branch (3/3) --

Calldata:

0xa9059cbb00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

transfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,0)

Caller:

0

Callvalue:

0

Returned: 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

We find that a call to WETH.transfer can end in three different ways, the last of which being a successful execution ending in return true. The first branch has nonzero callvalue, which ends up in a REVERT because transfer is not marked as payable. What about the second branch? Unfortunately, we can’t see what storage looks like, but in this case we can guess that the problem is that we have insufficient balance. Printing storage will come in a later release!

Recovering example input data for every branch can also be useful for gaining insight into contracts for which we have no source code. For example, we can take this random contract on etherscan, and symbolically explore it:

hevm symbolic --code $(seth code 0xFa9FfdF4F8b2D74526021Aa088486E5fA6F81132) --solver cvc4 --get-models

This time execution takes a little longer (around 6 minutes on my machine), and we end up exploring 53 branches! The full output is too long to show here, but let’s look at a branch that finishes successfully:

-- Branch (4/53) --

Calldata:

0xf3fef3a300000000000000000000000080000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Caller:

0

Callvalue:

0

Stopped

If we look up these signatures in 4byte.directory, we find that 0xf3fef3a3 is the signature for the function withdraw(address,uint256). Among the other execution paths we also find register(string,address) (branches 42-49) and userCount() (branches 51 and 52), deposit(address,uint256) (branches 19-21). This can give us some idea about what the contract is about, unless these names are purposefully misleading. Stepping the contract through the debugger can lead to further insight. In the future, this infrastructure could be extended to become a fully fledged decompiler of EVM code.

Equivalence checking

In many situations when writing programs, it is useful to be able to decide equivalence between two programs. For example, if we are developing a smart contract and come up with some clever gas optimization, it is important to ensure that the optimization does not change the contract’s semantics in unexpected ways. Consider the following example:

contract NaiveFib {

uint x = 1;

uint y = 1;

function next() public {

uint new_x = y;

uint new_y = x + y;

x = new_x;

y = new_y;

}

}

If we compile this simple program without activating the Solidity optimizer, we will soon realize that this code is quite inefficient. We are reading y twice, costing us a redundant SLOAD! We can rewrite next() more efficiently as:

contract OptimizedFib {

uint x = 1;

uint y = 1;

function next() public {

uint old_x = x;

uint old_y = y;

x = old_y;

y = old_y + old_x;

}

}

To check that our optimization is safe, we can compare the two versions for equivalence using hevm equivalence:

$ solc --bin-runtime Fib.sol -o .

$ hevm equivalence --code-a $(<NaiveFib.bin-runtime) --code-b $(<OptimizedFib)

Explored: 7 execution paths of A and: 7 paths of B.

No discrepancies found.

Note that for this simple example, the Solidity compiler is actually smart enough to perform this optimization for us. If we simply pass --optimize --optimizer-runs=9999 to original solc invocation, we will indeed end up with bytecode where the y read is cached. And if we are uncertain about the Solidity optimizer, we can double check its output using hevm equivalence, comparing the unoptimized and optimized versions!

Let’s look at another example, adapted from a bug report which demonstrates an error in the yul optimizer introduced in solc:0.6.0 (and promptly fixed in 0.6.1). In our version, the optimizer bug is only visible when the following yul code is called with the magic number 0xdeadbeef.

object "Runtime" {

code {

if eq(calldataload(0),0xdeadbeef) {

for {let i:= 0} lt(i,2) {i := add(i,1)}

{

let x

x := 1337

if gt(i,1) {

x := 42

break

}

mstore(0, x)

}

}

return(0,32)

}

}

The details of what’s going on in this code are not that important. It happens to be an extremely odd way of writing a function which returns 1337 if called with 0xdeadbeef, and 0 otherwise.

If we compile this with solc:0.6.0 with the optimizer activated, something goes horribly wrong.

Through the magic of nix, we can temporarily install a custom Solidity version without changing the solc of our path using dapp --nix-run:

dapp --nix-run solc-versions.solc_0_6_0 solc --strict-assembly --optimize solc061bug.yul

The optimized yul code looks like this:

object "Runtime" {

code {

if eq(calldataload(0), 0xdeadbeef) {

let i := 0

for { } lt(i, 2) { i := add(i, 1) }

{

if gt(i, 1) { break }

mstore(0, 0)

}

}

return(0, 32)

}

}

Suddenly, there is no trace of 1337, and we are left with an odd way of writing a function which always returns 0.

Running hevm equivalence against the two programs quickly catches the discrepancy between them:

hevm equivalence --code-a 63deadbeef600035141560355760005b600281101560335760018111156023576033565b60006000525b600181019050600f565b505b60206000f3 --code-b 63deadbeef600035141560415760005b6002811015603f57600061053990506001821115602f57602a905050603f565b80600052505b600181019050600f565b505b60206000f3

Not equal!

Counterexample:

Calldata:

0x00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000deadbeef0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Caller:

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Callvalue:

0

Although this example may appear quite artificial, it demonstrates an important point. Since the two programs only differ on the input 0xdeadbeef, it is very unlikely for a bug like this to be detected through manual testing, or even by comparing them against randomly generated inputs. But using symbolic execution we can find the discrepancy very quickly.

Limitations

The following environment or state parameters can be made symbolic in this release:

- stack

- calldata

- callvalue

- storage

- caller (msg.sender)

- memory

Crucially, other environment variables such as block.timestamp, tx.origin or blockheight are left concrete for now, but will be abstracted in future releases.

In this release, memory is modeled as a (concrete) list of symbolic values, which means that while you can read and write symbolic values to concrete memory locations, you cannot write or read from symbolic locations. Most of the time, when dealing with smart contracts written in Solidity using statically sized arguments, this is what is happening anyway. But if you are using hevm symbolic on some code which involves dynamically sized arguments, you might find that execution ends with an error unexpected symbolic argument. This is not a fundamental restriction to symbolic execution using hevm, but simply a decision to not include for this release, in order to reduce scope and retain good performance.

A similar restriction is placed on CALLs. The target of all CALLs must be concrete addresses in order to continue with the symbolic execution. If you are using hevm symbolic against live state, you will sometimes find it valuable to use ConcreteS as a storage model in order ensure you don’t end up calling a symbolic address.

Currently, it is not possible to use symbolic storage for multiple contracts. The storage model for any contract called by the starting contract will always be ConcreteS.

A classic problem one quickly runs into when doing symbolic execution is loops. If the loop condition depends on a symbolic argument, then naïvely exploring the possible execution paths will in the worst case not only result in an infinite regress, but an infinite regress on an unbounded number of branches. Although there are ways of getting around this problem, such as trying to infer loop invariants (as is done by Solidity’s SMT checker ), they are not included in this initial release. Instead, the number of times a particular piece of code can be revisited is bounded by the flag --max-iterations. This simple “bounded model checking” approach allows the execution engine to partially explore loops, but leaves it incapable of fully exploring the possibilities of certain loops.

Another limitation in this release is the encoding of dynamic calldata arguments. By default, hevm symbolic instantiates calldata to a symbolic byte buffer with a length of at most 1024, but can be specialized to conform to a particular function signature using the --sig flag. However, when using this method only statically sized arguments can be given. This means that you won’t be able to specialize calldata to match the function signature of foo(bytes a) for example.

You should not expect to be able to do much with precompiles with this release. The only one that is supported to be used with symbolic arguments is SHA256 at address 2, which is simply given as an uninterpreted function.

Future work

Besides addressing the obvious limitations discussed above, there are several directions future development can go from here.

Our immediate goal is to make hevm available as a proving back end to act. Besides the obvious benefit of being able to use hevm as a fast proving engine for formally verifying smart contracts, it would also make it easier to compare the behaviour of hevm against the more mature KEVM, and increase the confidence in hevm as a proving tool.

Another future direction would be in improving the interactive debugger. There are multiple ways to increase the usability and enrich the information provided when stepping through a contract symbolically.

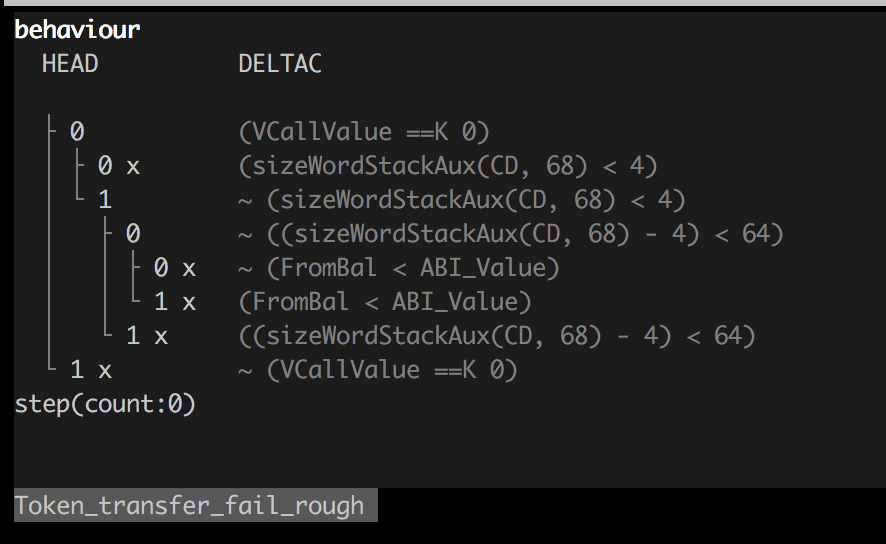

One improvement would be to add an overview display, which would show the user the tree of possible execution paths and their branching conditions similar to the one seen in klab:

A richer display of symbolic terms would also be valuable. Currently, all symbolic values are presented plainly as <symbolic>, but if we kept track of variable names and the operations applied to them we could display a syntax tree instead, as in balanceOf[msg.sender] - value. This way of tracking expressions would also bring the possibility of a general hevm decompiler closer to reality. Much of the infrastructure for pretty printing symbolic expressions is already in place, it has simply been decided to be out of scope of this initial release.

Another interesting prospect would be to integrate symbolic execution into the pipeline of dapp test. Currently, dapp test allows you to write unit tests and property based tests for smart contracts in Solidity. For an example of such tests, you can check out the ones written for the eth2 deposit contract.

Adding the ability for symbolic execution in dapp test would allow developers to specify and prove claims about their smart contracts without ever leaving the comfort of the Solidity language.

As discussed in limitations, hevm symbolic is currently poorly equipped to deal with unbounded loops. To combat this one would need to implement the ability to interweave EVM execution with custom trusted functions that update the EVM state, what we could call “trusted rewrites”. Along with specified loop invariants, trusted rewrites would allow hevm to reason about unbounded loops in a sound manner. Trusted rewrites could also allow the reuse parts of a symbolic execution, effectively opening up new ways to scale the formal verification process as a whole.

Adieu!

We hope this tutorial has given you a taste of symbolic execution with hevm, and some insight into the process of formal verification as a whole. For more information about hevm, check out the README, and if you have any questions or would like to discuss features, please raise an issue at the hevm repo or come chat at gitter or dapphub.chat/.