The SMTChecker is a formal verification module inside the Solidity compiler. Historically it has been complicated to run the SMTChecker on your own contracts, since you had to compile the compiler with an SMT/Horn solver, usually z3. We have been working on different solutions to this, and nowadays it is quite easy to run it.

The Solidity compiler ships binaries targeting 4 different systems, with different SMTChecker support:

- soljson.js, a WebAssembly binary that comes with z3.

- solc-macos, an OSX binary that comes with z3.

- solc-static-linux, a Linux binary that does not come with z3, but is able to dynamically load z3 at runtime if it is simply installed in the system.

- solc-windows.exe, a Windows binary that does not come with z3.

This means that if your development framework uses soljson.js or the OSX binary, or the Linux

binary and you have z3 installed, the SMTChecker should be available.

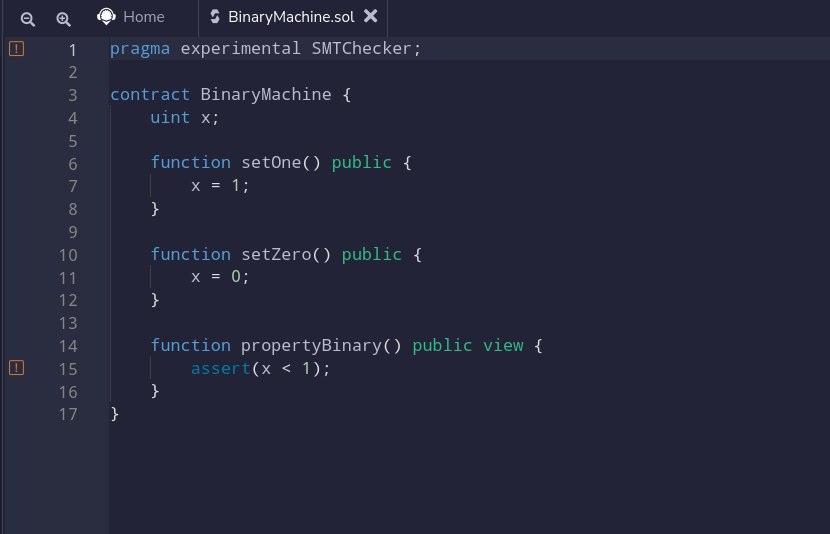

The old but still supported way to enable the tool is by using pragma experimental SMTChecker;

in your source code, but we are deprecating that in favor of the JSON field settings.modelChecker

and the --model-checker-* CLI options.

Solidity 0.9.0 will not accept the pragma anymore, only the JSON and CLI options.

Remix

Remix uses the WebAssembly binary, so the SMTChecker works out of the box.

It does not yet let you tweak the settings.modelChecker JSON field, but you can still

use the pragma version.

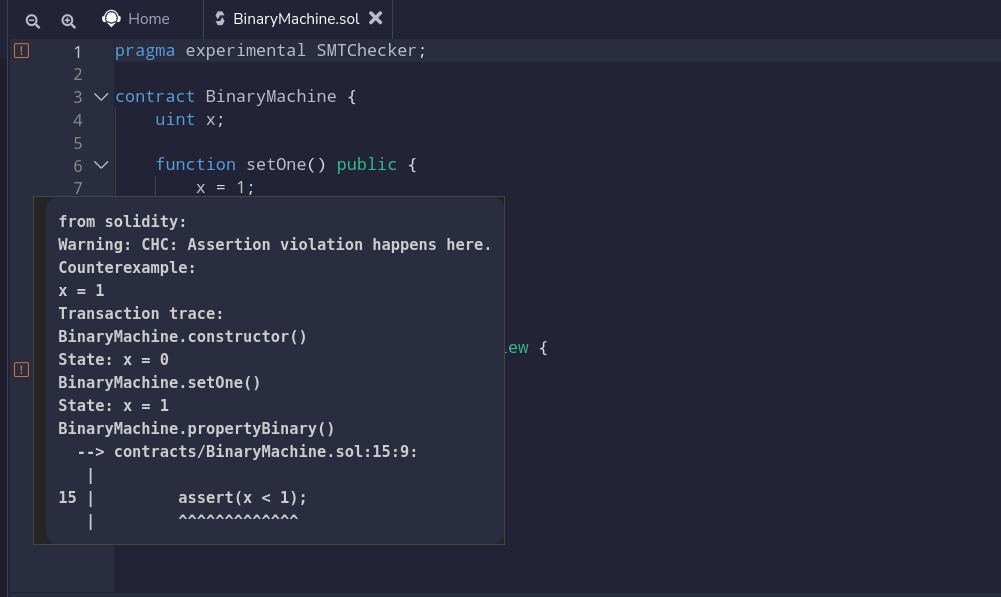

The warning on line 15 comes from the SMTChecker:

Note that the compilation time may increase considerably if you enable the SMTChecker, since the SMT solver will run in the background, trying to solve potentially several queries.

Dapptools

Dapptools has a tight integration with hevm

and makes it quite easy to apply formal verification.

Dapptools uses solc’s system’s binary via Nix, so if you use OSX you are

all set, and if you use Linux you just need to install the SMT solver z3.

This section is almost a transcript of the first part of my talk at Formal Verification in the Ethereum Ecosystem, where I demoed SMTChecker + Dapptools.

The easiest way to run the SMTChecker here is by using solc’s standard JSON interface.

You can generate a solc JSON input file of your Dapptools project with

$ dapp mk-standard-json &> smt.json

and then modify it manually to add the object

"modelChecker": {

"engine": "chc",

"contracts": {

"src/MyContract": [ "MyContract" ]

},

"targets": [ "assert" ]

}

Or use a one liner to do the same:

$ dapp mk-standard-json | jq '.settings += {"modelChecker": {"engine": "chc", "contracts": {"src/MyContract.sol": ["MyContract"]}, "targets": ["assert"]}}' &> smt.json

In the next release of Dapptools, this will become even easier:

DAPP_SMTCHECKER=1 dapp mk-standard-json

If the environment variable DAPP_SMTCHECKER is set to 1, dapp mk-standard-json already outputs the desired

input JSON file with standard values for the settings.modelChecker object.

You can simply modify them directly to change the model checker options.

Since the SMTChecker runs at Solidity’s compile time, now all you have to do is tell Dapptools to use that input JSON file and re-compile:

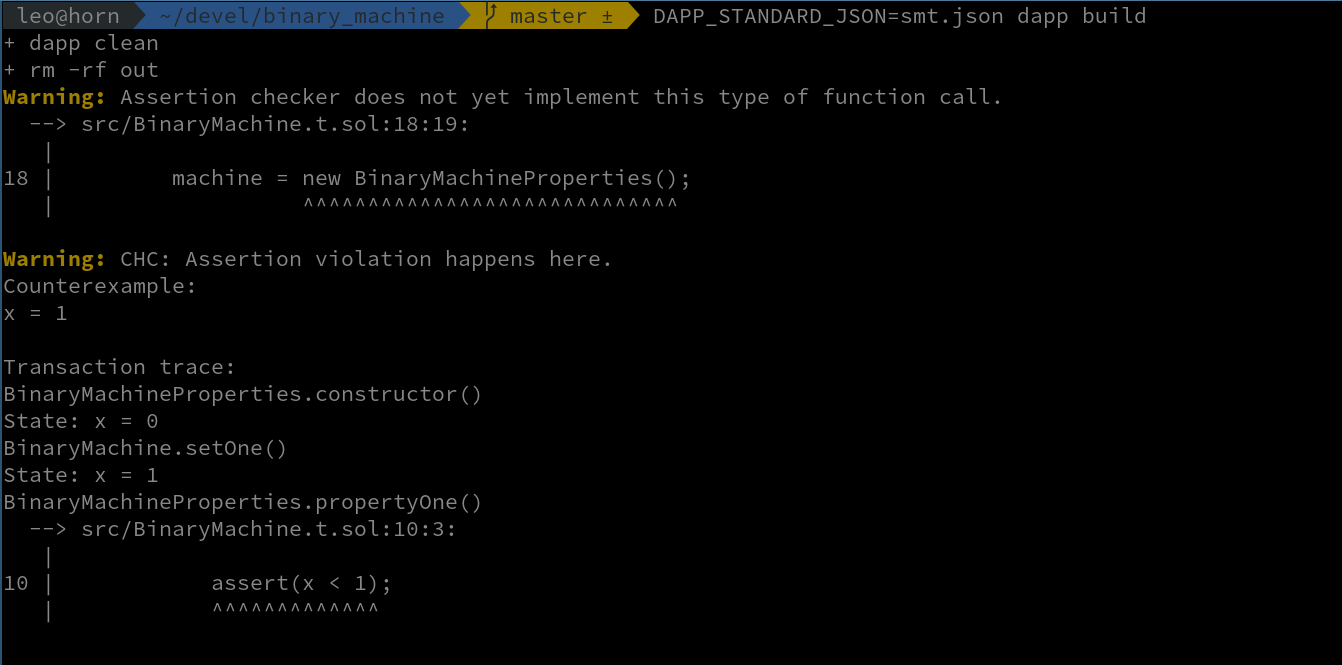

$ DAPP_STANDARD_JSON=smt.json dapp build

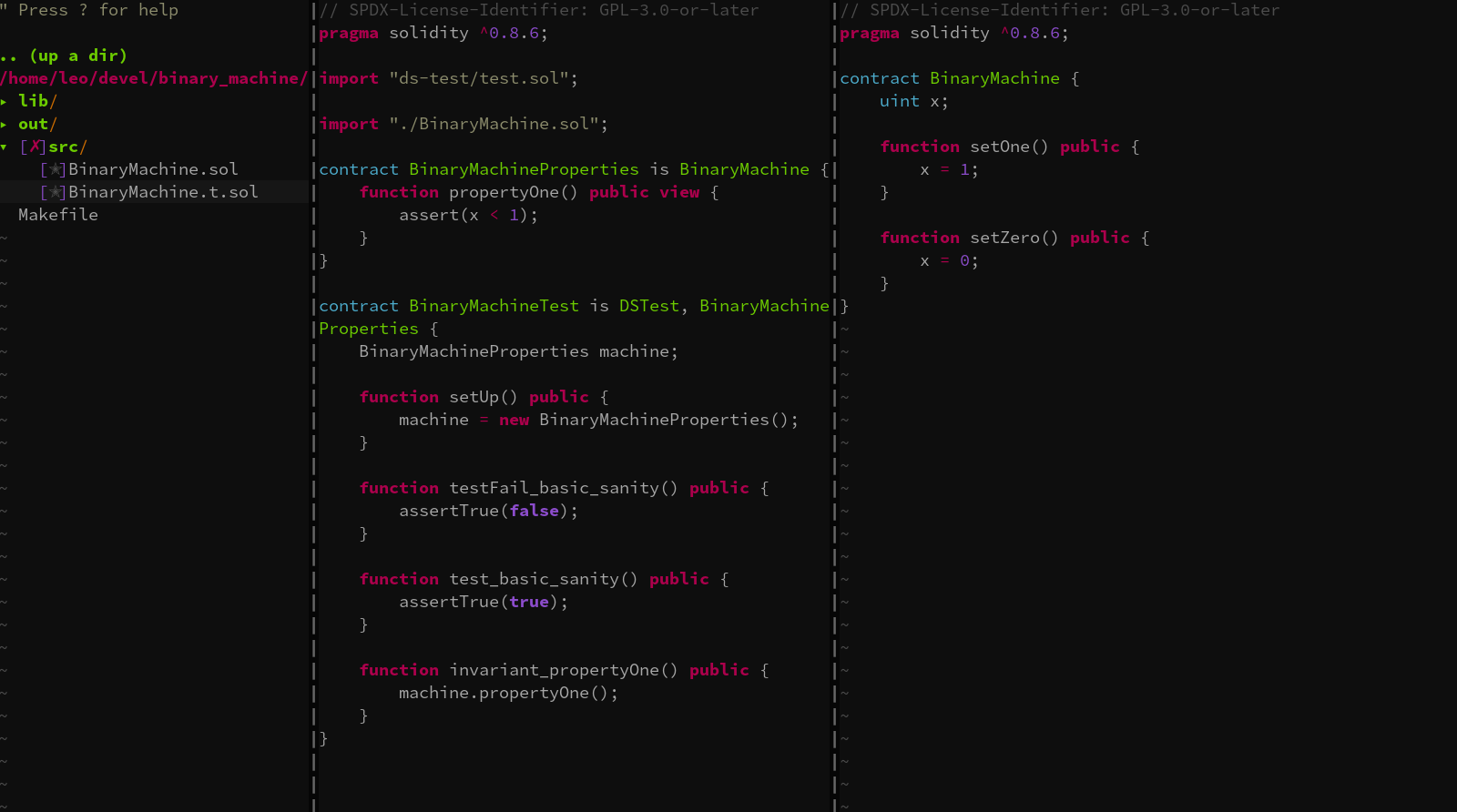

The SMTChecker does not handle Dapptools’ DSTest well, so it is recommended that you write a specific contract

with properties (assertions) you want to verify, and make that contract inherit from your main contract instead of calling it externally.

Then use this new contract as the target in the settings.modelChecker.contracts object above.

New object in the input JSON file:

"modelChecker": {

"engine": "chc",

"contracts": {

"src/BinaryMachine.t.sol": [ "BinaryMachineProperties" ]

},

"targets": [ "assert" ]

}

By combining the properties contract, which can also be seen as specification, and DSTest, one can use both the SMTChecker and hevm in the same setup.

SMTChecker analysis run:

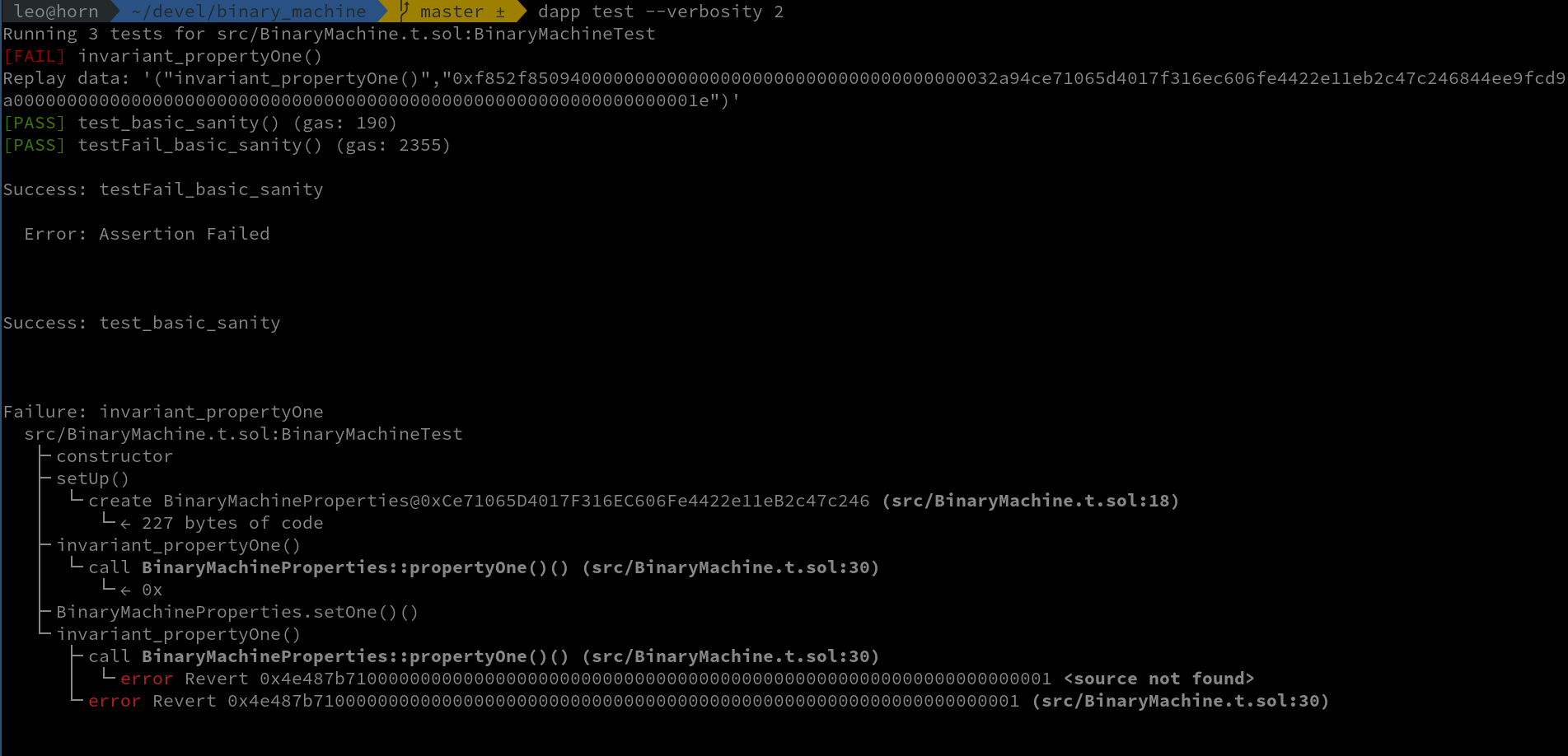

hevm fuzzer run:

Both tools show that our property is actually wrong, and give us a counterexample that breaks the assertion. Let’s fix the assertion and change the property function to:

function propertyOne() public view {

assert(x <= 2);

}

Now we don’t get a warning about the assertion anymore, which means that the solver managed to prove that the assertion is always true.

If we use Solidity 0.8.10 or greater, we can now ask the SMTChecker to give us any contract inductive invariants that the solver may have found:

"modelChecker": {

"engine": "chc",

"contracts": {

"src/BinaryMachine.t.sol": [ "BinaryMachineProperties" ]

},

"targets": [ "assert" ],

"invariants": [ "contract" ]

}

Here we tell Dapptools to use a solc different from its default (I downloaded the latest release):

DAPP_SOLC=./solc-static-linux DAPP_STANDARD_JSON=smt.json dapp build

Now we get:

Info: Contract invariant(s) for src/BinaryMachine.t.sol:BinaryMachineProperties:

!(x >= 2)

So the solver tells us not only that our assertion is true, but that there is

also a stronger property that is true: x < 2, instead of our x <= 2.

This property is automatically inferred by the Horn solver, together with

many other useful properties such as reentrancy properties and loop invariants.

Now let’s check a small but a bit more complex example:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0-or-later

pragma solidity ^0.8.6;

interface Unknown {

function callMe() external;

}

contract ExtCall {

uint x;

function setX(uint y) public {

x = y;

}

function xMut(Unknown u) public {

uint x_prev = x;

u.callMe();

// Can `x` change?

assert(x_prev == x);

}

}

We built the JSON input:

$ dapp mk-standard-json | jq '.settings += {"modelChecker": {"engine": "chc", "contracts": {"src/ExtCall.sol": ["ExtCall"]}, "targets": ["assert"]}}' &> smt.json

Since we are using smt.json just for the SMTChecker we can remove the ExtCall.t.sol source and the selected outputs, so that we get:

{

"language": "Solidity",

"sources": {

"src/ExtCall.sol": {

"urls": [

"src/ExtCall.sol"

]

}

},

"settings": {

"modelChecker": {

"engine": "chc",

"contracts": {

"src/ExtCall.sol": [

"ExtCall"

]

},

"targets": [

"assert"

]

}

}

}

Running

DAPP_SOLC=./solc-static-linux DAPP_STANDARD_JSON=smt.json dapp build

we get

Warning: CHC: Assertion violation happens here.

Counterexample:

x = 1

u = 0

x_prev = 0

Transaction trace:

ExtCall.constructor()

State: x = 0

ExtCall.xMut(0)

u.callme() -- untrusted external call, synthesized as:

ExtCall.setX(1) -- reentrant call

--> src/ExtCall.sol:18:3:

|

18 | assert(x_prev == x);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Now the counterexample tells us that x can actually change during an unsafe external call.

Furthermore, the solver synthesizes a reentrant call, performed by the externally called contract,

that eventually causes the assertion to fail.

One way to solve this is by applying a mutex modifier to both setX and xMut:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0-or-later

pragma solidity ^0.8.6;

interface Unknown {

function callme() external;

}

contract ExtCall {

uint x;

bool lock;

modifier mutex {

require(!lock);

lock = true;

_;

lock = false;

}

function setX(uint y) mutex public {

x = y;

}

function xMut(Unknown u) mutex public {

uint x_prev = x;

u.callme();

assert(x_prev == x);

}

}

Now the SMTChecker issues no warnings for the assertion, so it was proven safe.

Similarly to the previous example, we can also ask for a proof artifact here,

that being properties that are true for every unsafe external call in the contract.

That can be done with Solidity >=0.8.10 by requesting reentrancy invariants in

the settings.modelChecker object:

"invariants": [ "contract" ]

The property we get is:

Info: Reentrancy property(ies) for src/ExtCall.sol:ExtCall:

((lock' || !lock) && (<errorCode> <= 0) && (!lock || ((x' + ((- 1) * x)) = 0)))

<errorCode> = 0 -> no errors

<errorCode> = 1 -> Assertion failed at assert(x_prev == x)

The property may look a little complex, but it is rather simple.

Primed state variables (x') represent the state variable after the external

call returns, and non-primed state variables (x) represent its value before

the call is made.

The last term of the given conjunction is the most meaningful part of this property.

After a small simplification, we see that it states that lock -> x' = x, that is,

if the mutex variable lock is true at the moment of the external call,

x must be the same when the call returns.

Note that CHC is the recommended engine, and you are advised to always set the single contract you

want to be verified, as this helps the solver a lot. It may also be useful to set which verification

targets you would like to be verified, as well as a custom timeout if the solver is failing at your

properties.

You can find all these options and their description in the SMTChecker docs.

Other frameworks

The tool is of course not limited to only these two frameworks, and you can

pretty much use the same technique above to enable the SMTChecker in

development frameworks that allow the user to run solc in the standard JSON

mode.

Final Remarks

Hopefully we got to a point where at least running the SMTChecker is considered easy. However, using it in a way that gives meaningful results can still be tricky. It is important to be aware of the model checker options, to tell the tool which specific contracts need to be verified, and to use the best engine.

It is also important to write properties about the contract. Those can be used as specification, and can be verified (at least attempted) by multiple tools, as seen in the Dapptools example above.

Lastly, the tools cannot do more than the underlying solvers they use. In the Formal Verification industry it is essential to try as many engines, solvers, and configurations as possible when dealing with complex problems and properties. It is often the case that one different parameter can cause the solver to go the right way and prove/disprove a property that other solvers and configurations may timeout or run out of memory. Currently the SMTChecker only uses one solver and one configuration by default, which causes it to not be able to answer many properties. It is possible, however, to use different solvers and any desired configuration.

In the next blog post I will show how to do that, and present some experiments demonstrating how important it is to try different things when dealing with hard properties.

As usual, you are welcome to ask questions about the tool’s internals, how to use it best, and open bug reports.